Samoa

On the night of 6 August 1914 – 48 hours after Britain’s entry into World War I – the Governor-General of New Zealand received a secret cable from Britain, part of which read:

“If your Ministers desire, and feel themselves able to seize German wireless station at Samoa, we should feel that this was a great and urgent Imperial service…”

A radio transmitter located in the hills above Apia was capable of sending long-range Morse signals to Berlin. It could also communicate with Germany’s large naval fleet (over 90 warships). Great Britain wanted this threat neutralised and so New Zealand pledged their support the day after the despatch.

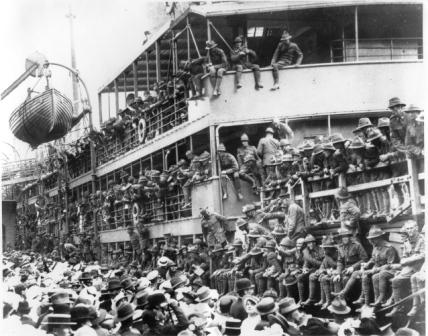

Very quickly a force 1,382 strong was mobilised and the ships landed at Apia on 29 August, complete with a regimental band. Without any resistance they took the inland wireless station and settled into life as an occupying garrison.

Gallipoli

New Zealand raised a force to fight in Europe and sent a brigade of mounted riflemen and a brigade of infantry, which – after meeting up with the Australians at Albany, Western Australia – was diverted to Egypt. These colonial troops from Australia and New Zealand were thought by the British to be uncouth and inferior soldiers, so when an operation was planned to take the Gallipoli peninsula, the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZACs) was chosen to take part in the diversionary attack halfway up the peninsula. The idea was to free up the straits of the Dardanelles so ships could get through to the Russian ports.

The New Zealand Infantry Brigade landed after the Australians on the morning of 25 April 1915 at a beach that would become known as ANZAC Cove. They were supposed to have been landed two kilometres south where the land was flat, but a navigational error put them ashore where gorse-choked gullies and steep hills made the attack very difficult. The New Zealand and Australian positions eventually ran along the line of Pope’s Hill, Quinn’s Post, and Courtney’s Post with the Ottoman Turkish positions sometimes only a few metres away.

After several months of fighting the New Zealanders advanced and took Chunuk Bair, the dominant feature and vital ground overlooking Anzac Cove to the west and the advance route to the Dardanelles to the east. The Wellington Battalion captured the heights in the early hours of 8 August and held the position against a series of Turkish counter-attacks. Their ranks would be decimated and relieving New Zealand units held the ground for two days until reinforced by two British units that would be pushed off the hill following a massed Turkish assault. The battle for Chunuk Bair was over and any Allied hope of capturing the peninsula was lost.

In December 1915, the entire position was evacuated after terrible casualties to both sides in the 8 months of fighting. The New Zealand casualty rate was 87% of the soldiers who fought. Far from being inferior soldiers, the New Zealand and Australian troops proved themselves to be some of the best fighting soldiers in the Empire. The day of the landings, 25 April, has become a national day of remembrance for Australian and New Zealand casualties of war – Anzac Day.

Sinai and Palestine

When the New Zealand Infantry Division sailed for France, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade (NZMR) remained in Egypt and fought in Sinai and Palestine from 1916 to 1918. The NZMR was an efficient and highly-mobile force equipped with mounted riflemen along with machine gunners, signallers, engineers, veterinary staff, a field ambulance, transport and artillery and even two Camel Companies. The Mounted Division again encountered the Ottoman Turks in places such as Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Jericho and the Jordan River.

By the time the Ottoman Turkish Army surrendered on 31 October 1918, the New Zealand Mounted Rifles Brigade had suffered some 1,700 casualties including over 500 dead.

Horses were the unsung heroes of the campaign. 10,230 were provided from New Zealand, mainly for service in Sinai and Palestine. Unfortunately, at the end of the campaign the men were unable to take their horses home, so in many cases – rather than leave them for the locals and possibly mistreatment – the men took them into the desert and, heartbreakingly, put them down.

Western Front

In April 1916, the New Zealand Infantry Division left Egypt for France, then moved into Belgium where they encountered the horrors and hardship of trench warfare against a large German fighting machine. They fought in many of the major battles in Belgium and France including the First Somme, Third Ypres (Passchendaele), Messines, and the Second Somme. They were a highly-regarded Division, often thrown into the front line with a well-deserved reputation of “getting the job done”. After March 1918 they achieved a number of striking successes including Bapaume (August), the crossing of the Canal du Nord (September) and the capture of the fortress town of Le Quesnoy (November).

The dominant weapon of World War I was the artillery gun. The 18-pounder was the standard light British and New Zealand Field Artillery piece of World War I. The other weapon which contributed to the stalemate of trench warfare was the machine gun which kept men pinned down in their trenches or cut them to pieces on attack.

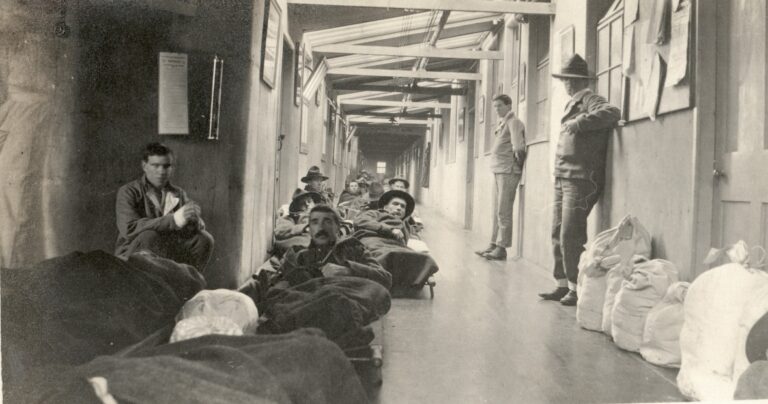

The troops got little respite and would spend eight days in a trench in truly appalling conditions. They would then spend the next eight days in billets behind the lines before moving back into the trenches again.

At war’s end on 11 November 1918 the Division headed to Germany, England and finally home in early 1919. Casualties were high – over 18,000 had died in World War I, with nearly 50,000 wounded. For those who came home, the horrors of war were often impossible to forget.